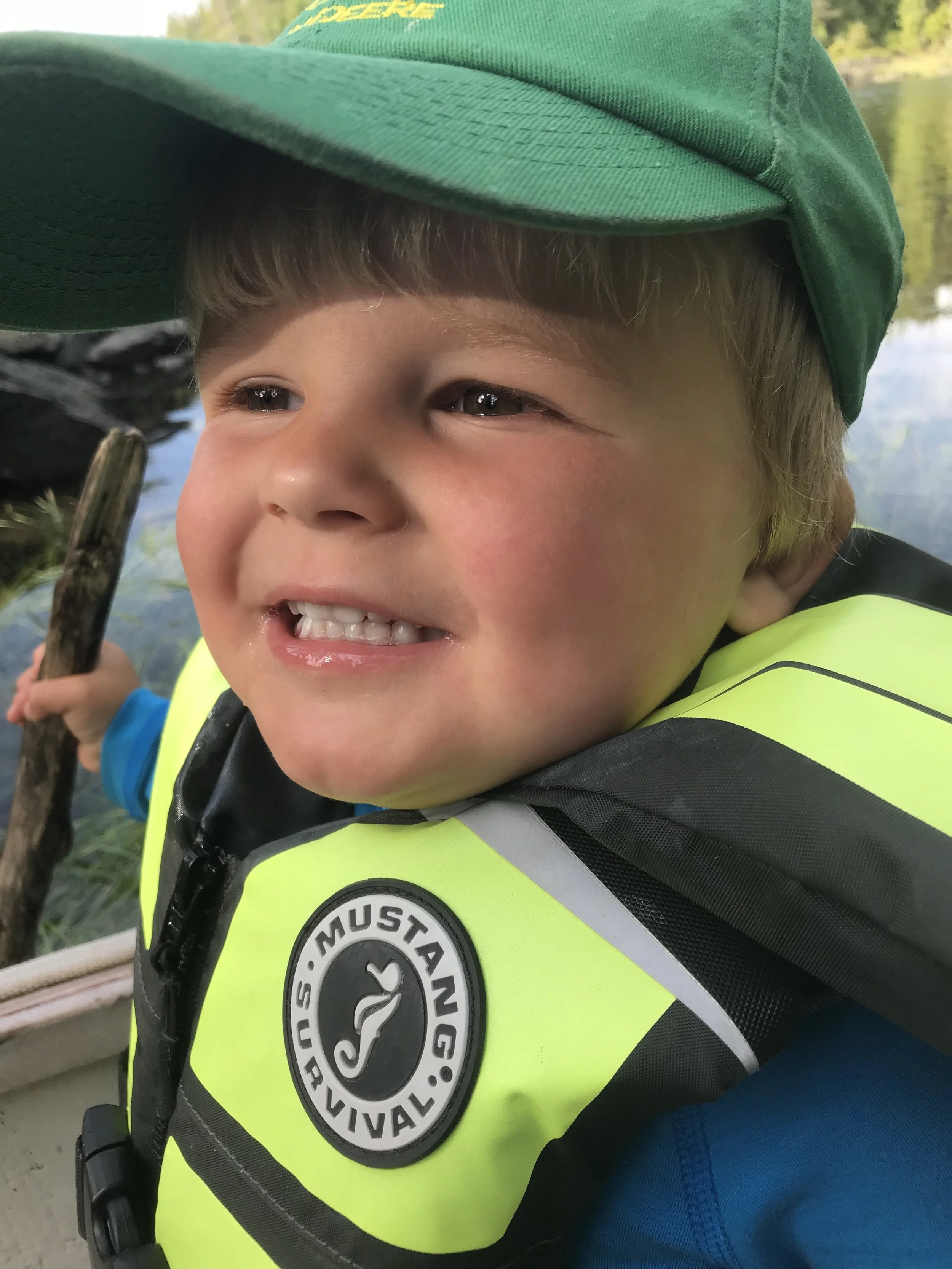

We’ve taken a break from the northern hemisphere winter and are on the North Island of New Zealand, living in a small camper van, and exploring a wildly different environment. Thanks to whining kids in the backseat, and a deluge outside, we made a recent detour that has so far been the highlight of our trip. Sometimes a 4-year-old knows best (as he regularly reminds us), and this time he was right: a small, family-run dairy farm was the perfect place to wait out the rain.

Without kids, we likely wouldn’t be traveling through New Zealand by van in the first place, and certainly wouldn’t have stopped at a place called The Farm simply for the novelty of it. We wouldn’t have met Mike, the farm’s lively owner, or seen the free-form operation he runs with his wife, children, and whoever else happens to be around on a given day. We’d likely be camped on a glacier in the snow rather than mucking through cow patties and watching pigs squabble over bread crumbs. We’d probably be fitter, and arguably tougher, at least in the physical realm, but no further from our comfort zone, no wiser to the many ways of making a home or building a family. Here, home consists of a sprawling farmhouse, 1,000 acres of marginal grazing land, outbuildings in various states of disrepair, two hundred dairy cows, a few dozen pigs, and a hodgepodge of cats, dogs, chickens, rabbits, and ponies. Family means more than just parents and kids. When I asked Mike how many children he has, he hesitated, and turned toward one of his sons. “What are we up to these days, anyway? We used to say 9, but I guess it’s really 11.” Only 4 are biological; the rest came to them by various means: a family friend’s death of cancer at 50, foster care, the fact that there are few places more welcoming to a traveler stranded on the roadside or a child in need of a home.

The scene is chaotic, but somehow it all works. The pigs get fed, the cows get milked, the floors are clean each morning. And everyone seems happy doing it, largely unbothered by the general state of entropy. All around the compound, there are motorbikes and old sheds and leaking roofs while every variety of animal grazes or rests nearby. Entire buildings look like someone’s junk drawer, housing an eclectic mix of the domestic and the industrial: sailing trophies perched atop a broken washing machine, an antelope head mounted next to an ancient piece of farm machinery, steel drums serving as a clothesline for a pair of jeans drying in the sun. There are tractors missing a track, cars missing a wheel, gates with broken latches, and doors coming off of their hinges. Yesterday morning, while we ate breakfast on the porch, a dozen cows ran frantically through the yard. A fence had been left open, or a latch was broken, or who knows what, but all of the cows had escaped during the night and Sunday morning was spent in pursuit of the wanderers. Most people would be floored, or at least annoyed, but when Mike drove up in a 4-wheeler pulling two trailers held together with wire and duct tape, he grinned hugely and shouted, “Good morning, how you all going today?” He and his sheep dog were covered in mud, sweating and panting respectively, and undeniably giddy. This was apparently the excitement they lived for, even if it meant that the many other tasks on his endless to-do list would have to wait another day. And yet he found time to show our boys how the milking shed worked, to instruct one of his trainees to get milk to feed the calves with us (also slightly askew as the boy’s floundering math skills left him with twice the volume he needed and later wondering why the calves weren’t more hungry), and to show us his giant pet steer, “Frosty” who weighs more than a ton and is as gentle as a house cat. What more could a kid wish for on a weekend? Does hospitality get any better than this? I can see why many people never leave, as it’s both the most welcoming and the most unassuming place I’ve ever visited. And on what other farm does morning milking happen at 10 am?

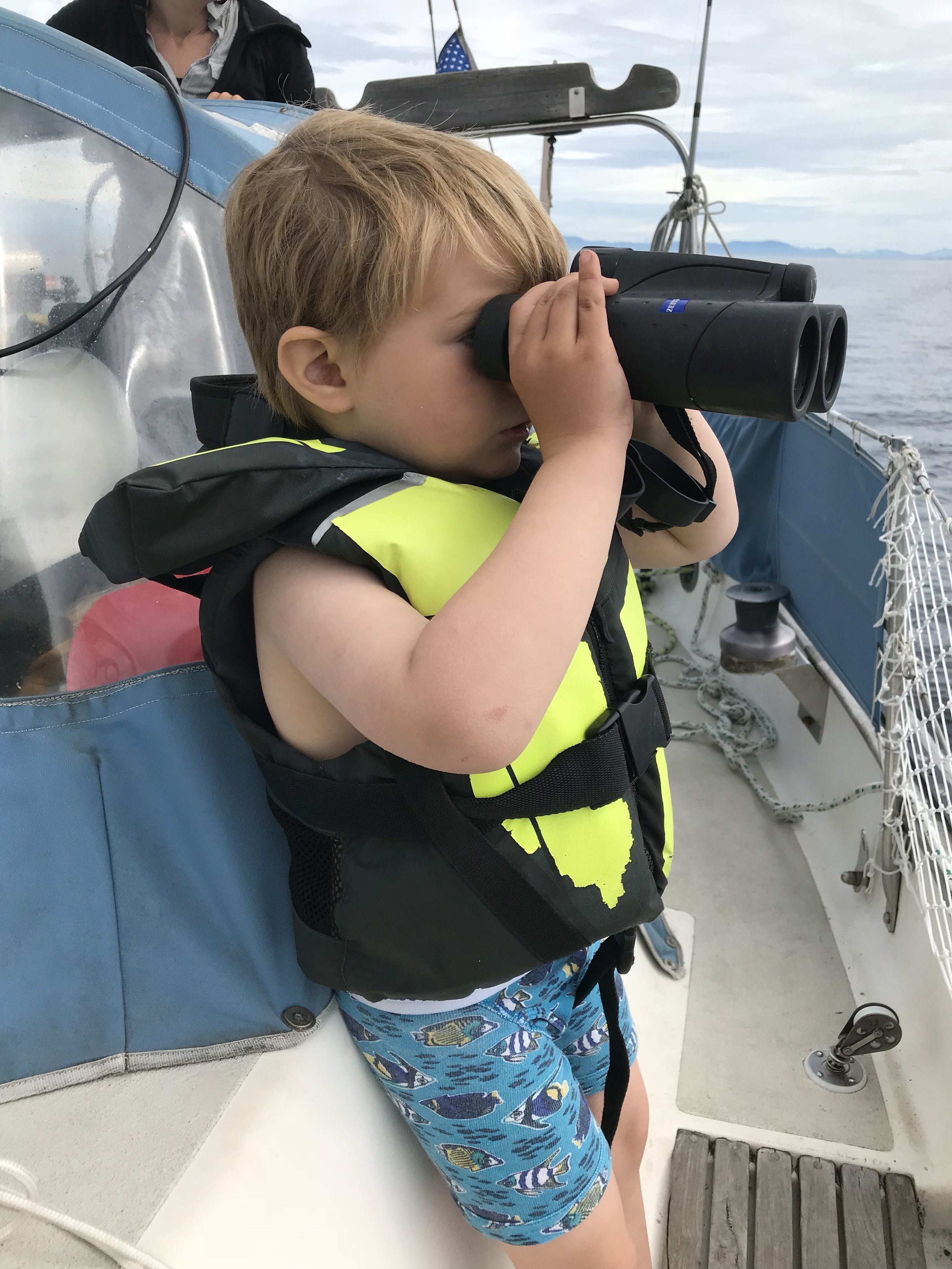

We’ll stay another day or two, then head a bit farther north before turning south again. After a long first week in Auckland, shopping for a camper van and getting sorted with the basic logistics of living in a new place, we’ve found a rhythm in our funny little van. We can all sleep inside, just barely, with the collapsed car seats extending the bed into a modified queen. Head-to-toe, with Pat’s legs serving as referee between the boys (they even manage to fight in their sleep). We’ve mostly been traveling through areas more rural than remote, but have stumbled onto our share of hiking trails and quiet coves. Of course there’s no shortage of new things to discover, especially from a kid’s perspective. We’ve waded thigh-deep in an underground stream, hiked along narrow sea bluffs, and wondered at the odd shape of the moon from the perspective of the southern hemisphere. The trees are exotic and the flowers abundant. Mornings are filled with birdsong that I don’t yet know. Some of the birds have come here for the winter warmth like we have, while others are just beginning their breeding season. I spotted my first Bar-tailed Godwit (an Arctic migrant) several days ago and last night heard the calls of a resident owl with a name that can’t help but make you smile (Morepork). Watching gannets dive is a favorite family pastime, or at least a favorite in my book.

We have our sights on the mountains of the South Island and will likely head there soon, but not until after a few more adventures on the northern coast, hopefully with a stop at the Miranda Shorebird Centre. It’s a sister organization to the Alaska Science Center (where I work), and they collaboratively track the amazing migrations of Bar-tailed Godwits and other shorebirds that transit the globe. For the next six weeks, we have no real itinerary, and only a little work to attend to. Life in a van with a 2- and a 4-year-old won’t suit us forever, but we’ll take it for now. Sending good winter wishes to everyone up north!